Upon witnessing his first NHL game at New York's Madison Square Garden in 1955, the Canadiens against the Rangers, Nobel Prize-winning novelist William Faulkner wrote in Sports Illustrated that Richard had “something of the passionate glittering fatal alien quality of snakes.”

And in a late 1950s profile for Maclean's magazine, Trent Frayne wrote of Richard on the rink, “Sometimes he scored them while lying flat on his back, with at least one defender clutching his stick, another hacking at his ankles and a third plucking thoughtfully at his sweater. … Modern hockey has produced many teams which stand out above their rivals but few individual players who stand out above the other individuals. For almost a decade, Richard has towered over them all, both as a goal-scorer and as a piece of property.”

The Richard Riot shook a province and a game to its very foundation. But sweep away the broken glass and clear the smoky air of 70 years ago and you’ll realize that one monumental night barely scratches the surface of one of the NHL’s greatest legends.

Five years ago, on the 20th anniversary of his father’s death, Maurice Richard Jr. considered an icon’s place in hockey history, and beyond.

“I don't think my father ever fully realized how important he was to Quebecers,” he said. “He was always surprised when he had a great round of applause or people were talking about him as if he were God. He wasn’t expecting that. He certainly didn’t play hockey to get that from the people. I’ve learned during my life that he had a very large family, one that was much bigger than just his children.”

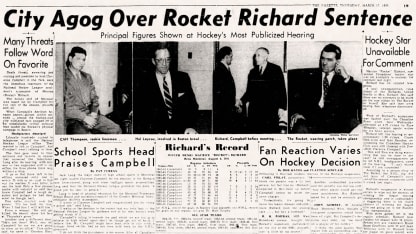

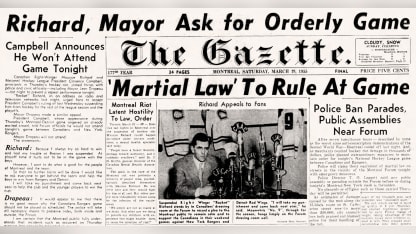

Top photo: front page of the March 18, 1955 edition of The Montreal Star, reporting on the violent chaos of the previous night at the Montreal Forum and in the streets of the city.