Darla Varrenti never imagined when saying goodbye on the phone to her teenage son, Nick, that it would be forever.

He’d been living with her in Mill Creek but had moved back to his native Pennsylvania 10 months prior to stay with his father, then divorced from his mother, mainly so he could play high school football with longtime buddies from his youth. That fateful Labor Day weekend in 2004, the 16-year-old starting nose guard played in a varsity football game on Friday night, filled in during a junior varsity contest on Saturday and then phoned Varrenti on Sunday before heading to bed in preparation for a holiday Monday practice.

But he never made it.

“His dad went to wake him, and he’d died in his sleep,” Varrenti said.

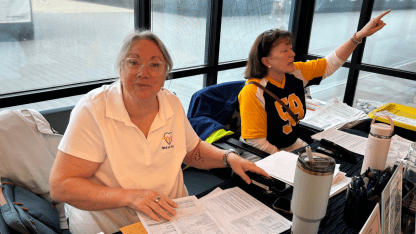

It was later discovered Nick had an undetected disease called hypertrophic myopathy, which resulted in an enlarged and thickened heart that restricted his blood flow and caused the cardiac arrest that killed him. On Saturday, Varrenti and her sister, Sue Apodaca, were at the Kraken Community Iceplex to stage the latest clinic by their two-decade-old Nick of Time Foundation, a nonprofit named after her late son and offering free heart screenings to thousands of young athletes ages 12-to-25 to prevent sudden cardiac arrest.

“Nick’s heart was 2 ½ times the size it should have been and if he’d have had a heart screening they would have found his heart was too big and that something was wrong,” said Varrenti, whose foundation gave screenings and additional CPR training to more than 250 young hockey players and other athletes at Saturday’s clinic hosted by the Kraken and Virginia Mason Franciscan Health, the team’s Medical Services Provider.

Such heart screening is typically not offered as part of routine sports physicals and can cost between $125 and $1,500.

But the foundation offsets that exclusively through donations and volunteer work by medical professionals. They suggest, but don’t mandate, that families receiving the screenings for their child make a $25 donation to the foundation, keeping their costs roughly in-line with a typical co-pay for a doctor’s visit.

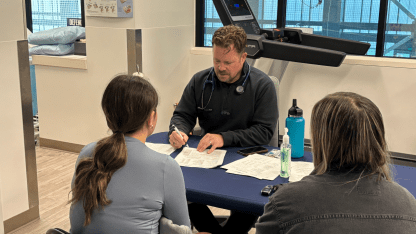

Each participant at Saturday’s clinic received an electrocardiogram (EKG) test to analyze their heart’s electrical activity. If additional screening was warranted, often the case about 10%-to-20% of the time, they also underwent a limited heart sounds examination or echocardiogram for further cardiac imaging.

Varrenti said about 700 of some 32,000 youngsters screened by Nick of Time since inception have needed the additional testing.

Participating athletes attending Saturday’s clinic also learned “Hands-only CPR” and how to use an Automated External Defibrillator.