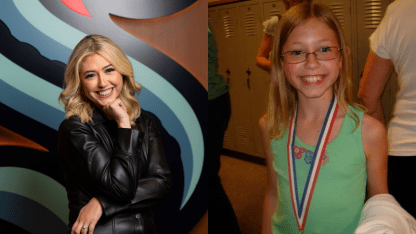

Shaw said her mother was “highly abusive in obscene ways” leaving the siblings grasping for control. Shaw was constantly told she was crazy. As a young girl, her mother bleached her hair in a short pixie-cut she wasn’t allowed to grow out. At 13, Shaw was bathed in paint thinner.

No explanation for it was given.

“I had to get really comfortable with pain and discomfort and get comfortable with myself,” Shaw said. “These days, I at least feel sane. But back then, I often had to fight to keep a grip on reality. Because my brothers and I were being gaslit into insanity.”

Shaw described her mother and stepfather’s house as a “bunker people” life with guns, safes, surveillance cameras, stockpiled emergency food and strict rules verging on cruelty.

“I wasn’t allowed to laugh,” Shaw said. “There was no laughing. My brothers and I were not allowed to physically play with each other. We were held in our rooms and could only talk via intercom in our house.

“We would just play video games on our computers. That’s how we had socialization -- through the phone.”

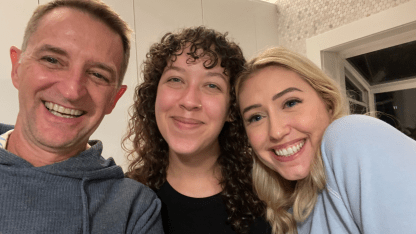

Shaw and her siblings became increasingly withdrawn; incorrectly attributed by her dad and others to struggling with the divorce. It wasn’t until her father took her to a community theater production his new wife, Deb, was performing in, that something within Shaw clicked.

“The minute the show was over, the curtain dropped and Piper just freaked out,” her father said. “She’s like ‘I want to do that.’”

Jesse Shaw said his daughter was always precocious, crawling from her crib at age 2 to steal ice cream from a spare refrigerator. And showy: By age 7 asking him to squirt an entire container of mustard into her mouth.

But theater brought out more.

“She could be a little socially awkward in a group of people,” her father said. “But put a microphone in her hand, she became a different person.”

Shaw performed in children’s productions before hundreds of people. She also played piano and the drums from her dad.

“She was pretty good, she had rhythm,” her father said. “To take it to the next level, we bought an electric drum set so she could practice and play. She was a real acoustic kid.”

Shaw’s father also bought her a guitar and enrolled her in voice lessons.

“Her biological mother was very resistant for Piper to take part in any of those things – it was always a battle,” her dad said. “Maybe that barrier to entry is why Piper tried so hard to be better at things. She had to make sure the performance was good.”

Shaw met a friend, Hannah Sims, who also performed children’s plays and whose dad ran maintenance for a St. Cloud theater. They’d dress in professional costumes and race around in a make-believe world.

“We were Spy Kids pretending to be on missions where we had to avoid my dad and other workers,” Sims said. “We would save different characters. There was one where it was animals, and we were protecting animals being held captive.”