In fact, former 17-year NHL stalwart Red Berenson had won a Stanley Cup with Montreal in 1965, then found himself back in Ann Arbor, Michigan the very next day to start working towards his own MBA at the university where he’d later coach. Botterill’s ensuing talks with Berenson helped convince him to get his MBA, which led to a front office career with three NHL teams and his own Stanley Cup victories, three of them with Pittsburgh as an assistant GM to Ray Shero and Jim Rutherford.

“I realize now that the fact I got out of playing in time was what let me go on to grad school and start this new career,” Botterill said. “To do the stuff I did in Pittsburgh and then here, the whole thing really was a blessing in disguise.”

For his former coach Berenson, now 85 and still living in Ann Arbor after coaching the Wolverines from 1984-2017, Botterill already had the perspective to know what he needed to do.

“I used to preach to players that this was why they were coming to school – that there’s life after hockey,” said Berenson, a six-time NHL all-star center and left wing who scored 261 career goals for Montreal, the New York Rangers, St. Louis and Detroit and later coached the Blues for three seasons – winning the Jack Adams Award in 1979-80. “It used to be that if you had a bachelor’s degree it would get you in most doors. But it was getting to the point that you needed a master’s degree.

“So, I was promoting to our players, especially the ones that were better than average students, to try and get an MBA or a law degree after they graduated or were done playing. And Jason was one of those kids who was a good listener. And he was interested in his whole life, not just the hockey part of his life.”

Part of that was Botterill’s upbringing in a Winnipeg, Manitoba home equally versed in athletics and academics. His father, Cal Botterill, was a pioneer of sorts in sports psychology and even co-wrote a book titled “Perspective: The Key To Life” the final seasons of his son’s pro career.

He'd moved the family from Edmonton, Alberta to Ottawa and then Winnipeg to take a full-time professor’s job at the local university there when a young Jason was only 4.

Botterill’s dad became rather widely known to Canadian sports fans as the psychologist for the country’s national hockey teams and several NHL squads. He'd also been a onetime junior level, college and minor pro player, though his on-ice exploits now arguably rank dead last among the family’s achievements.

That’s because Botterill’s mother, Doreen, was a two-time Canadian Olympic speed skater, competing under her maiden name of Doreen McCannell, in 1964 and 1968. She later became an elementary school physical education teacher and was inducted into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame in 1998.

Botterill’s sister, Jennifer, a Harvard University graduate three years younger than him, made it to four Winter Olympics in 1998, 2002, 2006 and 2010 as a star center for Canada’s national women’s hockey team – winning three gold medals and a silver. She also played professionally in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League ahead of embarking on her current broadcast career with Sportsnet and last November joined her mother with a Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame induction.

“I had a lot of competition in my family,” Botterill said.

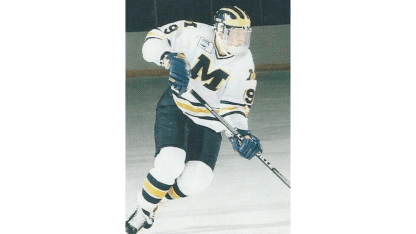

Not to be outdone, Botterill himself made history as the first player to ever win three consecutive gold medals at the IIHF World Junior Hockey Championships since the tournament became a sanctioned event in 1977, doing so for Canada from 1994 to 1996. It was also in 1996 that Botterill won a national championship at Michigan playing for Berenson.