There are times Patti Brinkley feels underestimated when some people first take her in.

It could be her 5-foot-1 stature or the fact the Kraken guest services manager works behind a main lobby counter at the Kraken Community Iceplex giving out information and selling everything from potato chips to pretzels and even skate rentals. The Woodinville resident admittedly gives off a few clues when working the register that she also happens to be a lawyer, a taekwondo black belt, and – oh yeah – taught Kraken mascot Buoy how to skate.

“I think people do tend to underestimate me,” Brinkley, 54, said with a chuckle. ‘I tend to be relatively chill and relaxed. And you know, I’m not the tallest.”

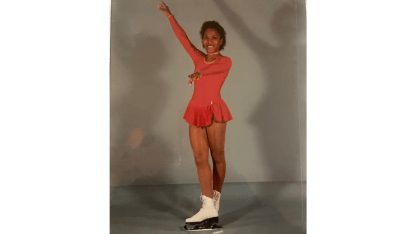

She’s also learned to shrug such things off. It comes with the territory of having been a rare African American figure skater, starting at age 5, in her native Chicago and continuing through her teens. It turned a few heads when she began coaching as well, starting in law school and resuming it later in her adulthood, eventually becoming skating director at the training facility for the American Hockey League’s Chicago Wolves.

Upon moving to the Seattle area some 18 years ago when her video game designer husband, Marc, took a job with Microsoft, she continued coaching and in 2012 became the skating director at the Olympic View Arena in Lynnwood.

Brinkley began working for the Kraken in May 2021 just ahead of their inaugural season.

With the team celebrating Black Hockey History Night, pres. by Amazon, at their Climate Pledge Arena game Tuesday against Detroit, Brinkley feels it’s important to represent her community in a way that gets people looking beyond first impressions. And like Black Hockey History Night itself, part of the Kraken’s “Common Thread” of themed games meant to honor communities not only during a single night but in continuing fashion throughout the season, Brinkley sees her representative role as part of an ongoing responsibility.

“There are times where I feel I’m definitely representing the community,” Brinkley said. “Definitely when I’m on the ice when I coach or teach. I’m trying to let some of the younger ones see that you can be on the ice. And that it’s a natural thing.

“Because there are a lot of kids who wouldn’t even think about being on the ice,” she added. “We have schools that come through here (on tours) and it’s not even a thought for the kids to skate because it’s not a part of their reality, you know? And it’s one of those things where it's like ‘No, you can do this. And it’s OK. It’s something that you can enjoy doing.’’’

Brinkley was one of “only two African American kids” figure skating in her area as a child in the 1970s. She became addicted to the sport, finding she missed coaching enough after getting her law degree from Chicago-Kent College of Law that she quit her first job in Illinois as a staff attorney for a firm providing legal counseling to clients making unemployment insurance claims. She immersed herself in coaching full-time from there, though upon moving to Seattle she worked for the state of Washington as an unemployment insurance claims adjustor for a few years.

She also found time to get into taekwondo, which her son, Lucas, 19, and daughter, Kaianne,16, had started doing a year earlier in 2014. They loved it and talked her into taking some lessons.

“I’m kind of notorious that once I start something I have to finish it,” Brinkley said.