Mel Bridgman was born in Trenton, Ontario on April 28, 1955 and raised in Thunder Bay, Ontario and Victoria, British Columbia.

The honor of being the first overall pick of the National Hockey League Entry Draft also comes with the burden of high expectations. Although he never became a prolific NHL scorer, Bridgman lived up to his billing in other ways.

Bridgman was one the team’s most reliable players during the transitional period of the mid-1970s to early 1980s. A model of consistency, Bridgman played nearly 1,000 games in the NHL, reaching the 20-goal mark six times, mostly as a third-line player. He was especially effective in big games, road tilts and during the playoffs.

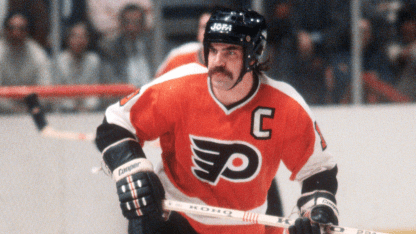

Possessing a winning combination of grit, toughness, two-way play, leadership and intelligence, Bridgman was a clear-cut choice to succeed Bobby Clarke as Flyers captain when the Hall of Fame center became a playing assistant coach.

The versatile Bridgman switched off readily between center and left wing and could anchor checking or scoring lines without missing a beat.

“He had a special determination. When Mel went after the puck, he was like a bulldog. He had his mind set. If you put a wall between him and his assignment, you would lose that wall,” the late Pat Quinn in The Greatest Players and Moments of the Philadelphia Flyers.

Coming from a family where education was highly valued, Bridgman took college classes at Villanova University and the University of Pennsylvania during his playing career and went on to earn his Masters of Business

Administration at the Wharton School of Business.

Going West

Melvin John Bridgman was born in Trenton, Ontario, on April 28, 1955, and spent most of his early years in Thunder Bay, Ontario. When he was a teenager, his father, a meteorologist, relocated the family west after he was transferred from his job in the Ontario bureau to one located in Victoria, British Columbia.

Mel, a shy child, took a little while to adjust to his new home. A common bond he shared with his dad was their mutual love for hockey. Mel started playing youth hockey while in Thunder Bay and brought his equipment with him to Victoria, playing at the first opportunity. Bridgman’s parents supported his

participation with the understanding that Mel had to keep his grades in school strong to play hockey.

“My father was a huge Canadiens fan, so the first time I played against them in Montreal (on October 18, 1975) was awesome. It was just a great thrill and it was probably the most nervous I have ever been on the ice,” Bridgman told USAHockey.com.

At the age of 16, Bridgman was recruited from the Nanaimo Clippers of the British Columbia Junior Hockey League to play for the Victoria Cougars of the WCHL. Splitting time between Nanaimo (where he scored 37 goals and 87 points in 49 games in ‘72-’73) and Victoria, Bridgman suited up in eight games for Victoria during the 1971-72 and 1972-73 seasons, scoring once.

In 1973-74, the same year the Flyers won their first Stanley Cup, Bridgman emerged as one of Victoria’s top players, posting 26 goals and 39 assists for 65 points in 62 games with the Cougars. The next year, he set a league scoring record (since broken) with a remarkable 66 goals, 91 assists and 157 points to go along with 175 penalty minutes.

Although he wasn’t the swiftest of skaters and didn’t possess an overpowering shot, Bridgman’s physical play, smarts and good hands in close to the net made up for whatever gifts he may have lacked.

Bridgman’s magnificent play in 1974-’75 helped launch Victoria from fifth place in their division to the best record in the WCHL. Over the last six games of the season, he scored an extraordinary 25 points. He continued his dominance in the playoffs, lighting the lamp 12 times in 12 games, to go along with a half-

dozen helpers.

Not surprisingly, scouts turned out in droves to see Bridgman play. That season, Bridgman also played for silver medal-winning Team Canada in the second-ever World Junior Championships (then an unofficial International Ice Hockey Federation tournament).

Years later, Bridgman looked back fondly on his junior career.

“I learned a lot about playing the game in Victoria – going into the corners and playing in traffic without worrying about the consequences. I had good coaches

and good teammates. It was a great foundation to build from, hockey wise and personally,” he said.

Returning East

On June 4, 1975, shortly after the Flyers defeated the Buffalo Sabres to win their second Stanley Cup, General Manager Keith Allen announced the team had traded forward Bill Clement, defensive prospect Don McLean and cash considerations to the struggling Washington Capitals in exchange for the first

overall pick in the 1975 NHL Entry Draft.

All along, the Broad Street Bullies champions honed in on a single player – Mel Bridgman.

“The only thing he might lack is confidence,” Flyers scout Gerry Melnyk said in the Flyers 1975-76 yearbook. “But that will come.”

Bridgman became the first British Columbia resident to be selected first overall in the NHL Draft. To date, the 1975 Draft marked the only time in Flyers history that the team picked first in the Draft.

“Being picked by the Stanley Cup champions surprised me,” he said to Stan Fischler. “I thought I was going (with the third pick) to the California Seals.”

The prestige associated with being the first pick of the 1975 draft meant more to Bridgman years later than it did as a young player.

“When you are in the middle of a career, you don’t think too much about it because you’re enjoying the game so much,” he reflected to USA Hockey.

“But when you consider the number of teams and players we had then, maybe 40 to 50 new players entered the league every year. To be considered one of the best,it just means more to me as the years pass.”

The Flyers had competition for Bridgman’s services. The Denver Spurs of the rival World Hockey Association selected the Victoria center with the fourth overall pick of the 1975 WHA Draft.

Although Spurs owner Ivan Mullenix publicly pledged to make Bridgman an offer he couldn’t refuse, the 20-year-old center quickly chose the defending Stanley Cup champions over the fledgling Denver franchise. He signed a five-year contract with the Flyers, worth $500,000.

Bridgman made a wise decision to spurn the Spurs. The first-year team struggled badly at the gate, briefly moved to Ottawa, Ontario (where they were rechristened the Ottawa Civics) and then folded mid-season in their first year after just 41 games played.

Flyers rookie standout

Meanwhile, Bridgman got acclimated to life in the National Hockey League. Playing for the Flyers, who were loaded with forward talent on the top two lines, the rookie was allowed to learn his craft in the background of stars like Bobby Clarke, Bill Barber, Reggie Leach and Rick MacLeish.

At first, Bridgman’s introverted nature was mistaken for aloofness by some of his Philadelphia teammates. He arrived at training camp feeling homesick and, not wanting to step on any of the veterans’ toes, he rarely made eye contact or spoke unless spoken to.

“Mel was very shy and withdrawn. He was pretty nervous and unsure of himself. The veterans on the team really kidded him a lot,” the late Ross Lonsberry said in Greatest Players and Moments.

“Bridgman did a lot of growing up between that rookie training camp and the [1976] playoffs. He came out of his shell and became one of us.”

Recognizing that Bridgman needed to feel like he belonged in the NHL, Flyers captain Clarke took the rookie under his wing. For a full week, Clarke asked Bridgman to tag along with him.

“I spent a lot of time with Bobby that week,” Bridgman recounted in the 1975-76 Yearbook. “Everywhere he went, I went along with him. I even went with him when he was attending to some personal business. The way he looked after me made me feel a little more at ease.”

While Bridgman’s teammates saw that he lacked self-confidence, the news would have come as a surprise to the Flyers opponents. It didn’t take Bridgman long to earn his wings as a full-fledged member of the Broad Street Bullies.

On opening night of the 1975-76 season, Bridgman made his NHL debut against the Capitals, playing left wing on a line with Orest Kindrachuk and Don “Big Bird” Saleski. Late in the second period, with the Flyers leading 3-2, Saleski worked the puck back to defenseman Joe Watson.

The elder Watson brother sent the puck at the net, where Bridgman was camped out in front of goaltender Michel Belhumeur. A split second later, Mel Bridgman scored his first NHL goal. He ended up with four shots on goal in a game won by the Flyers.

Two nights later, Bridgman duplicated the feat in a 9-5 road victory against the Minnesota North Stars.

This time, in the midst of a four-goal first period by the Flyers, he followed up on a Saleski scoring chance to bang the puck home past North Stars goalie Paul Harrison.

On October 30, 1975, Bridgman and the Flyers traveled to Toronto to take on the Maple Leafs. In the first installment of a nasty season series that gave way to a playoff war, the Broad Street Bullies humiliated the Leafs by a 6-2 score in a game marked by 129 penalty minutes whistled by referee Dave Newell and a

slew of fights and stick infractions.

In the process, the Flyers outshot the Leafs 47 to 21.

The game was tied 1-1 after the first period. Seven minutes into the second period, Bridgman scored a powerplay goal to put the Flyers up 2-1. Barely two minutes later, Barber extended the lead to 3-1.

On the next shift, Toronto defenseman Brian Glennie picked a fight with Bridgman. Dropping the gloves for the first time in the NHL, Bridgman got the better of the solidly built Glennie. Moments later, Bob

Kelly scored to make the game 4-1.

That ended the night for beleaguered Toronto goaltender Wayne Thomas, who was booed lustily by 17,077 howling Maple Leafs partisans as he skated slowly to the bench.

Early in the third period, Bridgman scored his second goal of the game, once again getting himself in a good scoring position in front of the net. Bridgman, who registered five shots on goal, earned third-star honors for the game.

He followed that up with a goal and an assist in the next game, an 8-1 thrashing of the Boston Bruins on Spectrum ice, then scored two more goals plus an assist the following night as the Flyers mercilessly whipped the hapless Kansas City Scouts by a 10-0 score. Bridgman was named the third star of the game for the second time in three nights.

Heading back out on the road, the Flyers faced a tough test against the Chicago Blackhawks, settling for a 4-4 tie after leading 4-1 midway through the third period. Bridgman kept his point streak alive with an assist and once again took third star honors.

Bridgman’s hot streak was snapped in the next game, a 1-1 tie with the Los Angeles Kings at the Spectrum. As so often happens with rookies, Bridgman went into an offensive slump as opposing teams realized they couldn’t only concentrate on trying to contain the Clarke and MacLeish lines. Over the next 11 games, Bridgman failed to register a point.

Flyers coach Fred Shero dropped Bridgman to the fourth line with veterans Terry Crisp and Bob Kelly in order to alleviate some of the pressure the rookie

started putting on himself to score. Later, he centered a line with Lonsberry and Gary Dornhoefer, when MacLeish was lost to a frightful neck injury.

Bridgman’s willingness to concentrate on the defensive aspects of hockey and play a straightforward, physical style impressed Crisp.

“He was a super kid,” Crisp said to Fischler. “He did everything you could ask of him and it didn’t phase him at all.”

Despite the absence of superstar goaltender Bernie Parent (lost to a back injury that required surgery) for much of the season, the Flyers defeated Russia’s mighty Red Army team in a battle for global club-team hockey supremacy. The Broad Street Bullies then went on to tie the NHL record for the longest unbeaten

streak, matching a 23-game streak set by the Boston Bruins in 1940-41.

The Flyers easily won first place in the Patrick Division with 118 points. At the Spectrum ice, Philly was virtually unbeatable, posting a phenomenal 36-2-2 record.

All the while, Bridgman learned from the Flyers’ leadership group what it takes to be a champion. He finished his rookie season with 23 goals, 50 points, 86 penalty minutes and a plus-20 rating. But personal stats and regular season wins meant little in Philadelphia.

“The focus all along was to get back to the Stanley Cup Finals. To do that, we went out and tried to play a strong 60 minutes of hockey every night. The record takes care of itself when you do that,” Bridgman said.

“I learned a lot about winning and being a winner. That kind of development is just as important as individual development and statistics. Would it have been nice to play on a team where I would have gotten more ice time and more power play time? Maybe. But I also know that a big reason for my longevity in the NHL is that I developed in a winning environment.”

Toronto nemesis

The Flyers and Maple Leafs met in the 1976 Stanley Cup Quarterfinals. As expected, Philadelphia won the first two games at the Spectrum. Eight minutes into the opening period of Game One, with the Flyers in the middle of a line change, Bridgman picked up an assist on a Reggie Leach goal. In the third period, the rookie earned a power play assist on a Gary Dornhoefer goal.

Bernie Parent took care of the rest, turning aside 23 of 24 shots for a 4-1 win.

In Game Two, Parent stopped 31 of 32 shots to backstop a 3-1 win. Bridgman once again earned an assist, this time setting up Lonsberry on what proved to be the game winning goal. The scene then shifted back to Maple Leaf Gardens.

As with the October meeting, referee Dave Newell was unable to keep control of the game, no matter how often he blew the whistle and ejected players. High sticks, elbows and fists flew on both sides throughout the game, and Toronto ended up with 16 power plays to just three for the Flyers. Bridgman was at the

center of a huge controversy.

The fuse was lit when the Maple Leafs’ Kurt Walker speared Flyers enforcer Dave Schultz early in the first period, triggering the first of many brawls and earning a gross misconduct penalty.

Throughout the Flyers season series with the Leafs, Philly made a point of trying to hit Toronto’s two Swedish imports, winger Inge Hammarstrom and defenseman Borje Salming, every time they touched the puck.

The finesse-oriented Hammarstrom, who later became a Flyers scout, did not respond. Salming did – both with his skill and his fists.

Toronto scored four powerplay goals in the first period and a half of play to take a 4-1 lead. Goals by Dornhoefer and Jimmy Watson just 13 seconds apart quickly trimmed the deficit to 4-3 and triggered a spirited fight seconds after the next faceoff between wildmen Jack McIlhargey of the Flyers and Dave

“Tiger” Williams of Toronto.

With the Toronto crowd still in a frenzy, Saleski was whistled off for tripping, barking at Newell on the way to the penalty box. As he stood in the box, a Toronto fan tossed a chunk of ice cubes at him from behind. Furious, Saleski whirled around and confronted the fan.

A Toronto police officer raced over and grabbed Saleski’s stick, who tried to wrestle it back, as the scene around Saleski continued to escalate.

Sensing his teammate was in danger, the normally non-combative Joe Watson led the charge toward the penalty box. From the ice, Watson swung his stick over the glass, striking policeman Art Malloy in the shoulder.

Order was restored, but only temporarily. The next shift after Toronto’s fifth power play goal of the game made the score 5-3, Bridgman nailed Salming behind the Toronto net. Toronto won the game 5-4.

The next day, Ontario district attorney Roy McMurtry announced that he was

filing criminal charges against Bridgman (“assault with intent to commit bodily harm”), Saleski and Joe Watson. The three players were forced to turn themselves in to police, fingerprinted and then released.

Forty-eight hours after the Game Three debacle, Bridgman answered for the Flyers the best way he knew how. Booed every time he touched the puck, Bridgman scored two goals and threw his weight around with abandon. Unfortunately, a poor second period doomed the Flyers to a 4-3 defeat, sending the series back to Philadelphia.

The Flyers ran roughshod over the Leafs in Game Five at the Spectrum, capturing a 7-1 victory. Although he failed to register a point in this game, Bridgman had five shots on goal and was a force down low in the offensive zone the entire game, keeping Toronto hemmed in their own zone.

As happened earlier in the series, Toronto played meekly in Philadelphia only to come out roaring at home. In yet another fight-filled tilt that spilled over into the stands, Toronto won a wild 8-5 contest to force a seventh game.

Bridgman dropped the gloves with Toronto winger Kurt Walker, himself no stranger to fisticuffs. Earlier in the game, a Toronto fan struck Schultz as he was escorted to the locker room on a misconduct penalty.

Once again, the Flyers players raced over to defend their teammate. In the ensuing melee, Bob Kelly threw a glove into the stands, accidentally striking a female usher. She was not injured, The next day, however, charges were filed against Kelly, too.

NHL commissioner Clarence Campbell, who had a legal background and frequently clashed with the Flyers, spoke out against the series of criminal charges, saying the Philadelphia players had merely acted to protect themselves in each instance and, in Bridgman’s case, it was a routine (if one-sided) fight.

The charges against Bridgman and Saleski were eventually dropped, while Watson paid a $750 fine and Kelly a $250 fine.

The seventh and deciding game was played in Philadelphia on April 25, 1976. Mel Bridgman delivered the final verdict in the Flyers favor. With the Flyers trailing 2-1, the rookie spearheaded a magnificent second period, scoring a pair of goals and winning almost every faceoff he took. Philadelphia stormed

back to win the game 7-3 and emerged victorious in one of the most brutal NHL playoff series in history.

Bridgman earned first star honors in the deciding tilt.

In the semifinals, the Flyers were stunned on home ice in the opener against the Boston Bruins before winning the next game in overtime. Even so the Flyers seemed to be in trouble, heading back to Boston Garden, a venue where Philly rarely won.

Things looked especially troubling because Parent’s deteriorating physical condition forced him back to the sidelines.In Game Three, Bridgman had a monstrous performance, scoring the game winning goal on a Larry Goodenough rebound early in the third period and adding a pair of helpers to take first-star honors in a virtual must-win game.

Two nights later, he did it again, erasing an early 1-0 deficit with a goal and

adding an assist on a much-needed insurance goal in the waning minutes of the third period. Reggie Leach took care of the rest in Game Five, scoring five times to send the Flyers back to the Stanley Cup Finals.

Unfortunately, the Canadiens won in four straight games (three of which were decided by a single goal) to dethrone the Flyers as champions.

A Time of Transition

The 1976-77 to 1978-79 seasons marked a slow transitional period for the Philadelphia Flyers. Slowly but surely, GM Keith Allen dismantled the nucleus of the Broad Street Bullies. The team gradually slipped in the standings and was eliminated by Boston in the semifinals two straight years, followed by a first-round loss to the Rangers in 1978-79.

In his second NHL season, Bridgman continued to shuttle between left wing and center, scoring 19 goals and 57 points on the third line as the Flyers won the Patrick Division with 112 points. He was limited by a severe charley horse late in the season and missed the first two games of the Flyers-Maple Leafs

quarterfinal playoff rematch.

The Flyers suffered a pair of home losses, before rallying to win the next four games in a row.

In a must-win Game Four, the Flyers trailed 5-2 midway through the third period, when Bridgman stuffed home a Bob Dailey rebound. The Flyers gained new life, going on to win the game in OT. In the clinching sixth game, with the Flyers losing 3-2 in the third period, Bridgman’s work in the offensive zone forced Toronto defenseman Mike Pelyk to take a penalty.

Rick MacLeish scored on the ensuing powerplay to tie the game, before Jimmy Watson won the game and series late in regulation. In the conference finals, the Flyers fell to the Boston Bruins in a four-game sweep. A hobbled Bridgman dressed in three games.

As a third year player in 1977-78, Bridgman began to emerge as a more vocal leader in the locker room. The player, now sporting a thick mustache on his formerly clean-shaven visage, recognized that the team needed his physical presence more than his scoring. With Dave Schultz traded a year earlier and Paul Holmgren injured for a significant portion of the season, Bridgman stepped up his aggressiveness to post a career-high 203 penalty minutes.

While his offensive output slipped to 16 goals and 48 points, he played strong two-way hockey in a checking role to post a solid plus-26 rating. In what proved to be Fred Shero’s final season as Flyers’ coach, Philly posted 105 points and finished in second place in the Patrick Division.

The club made it to semifinals again in the playoffs, losing to Boston in five games. Bridgman had eight points and 36 penalty minutes in 12 playoff games.

After Shero left to become the coach and general manager of the New York Rangers, he publicly praised Bridgman as one of his favorite players over the latter part of his Flyers coaching tenure.

“Mel was worth what the Flyers gave up to get him,” said Shero. “He could do so many things well, but best of all, he was big and strong. He wasn’t afraid to go after the puck and take a shot to get it, and he could give a shot to knock someone off the puck.”

In 1978-79, the Flyers scuffled under new head coach Bob McCammon, who was soon demoted to coach the AHL Maine Mariners while Mariners head coach Pat Quinn became the Flyers bench boss.