John O’Connell walks from his home to the local bus stop with his hockey bag and stick in tow and sunglasses on.

O’Connell, who is 62 years old, takes the bus from his hometown of Toms River, New Jersey into Penn Station in Manhattan. From there, he rides a train to Newark Penn Station. Another train ride lands him in Boonton, New Jersey. At that point he hops in an Uber to arrive at the Bridgewater Ice Arena.

In total, it takes roughly four hours of travel time, all just for O’Connell to play hockey for an hour.

After the exhaustive travel, O'Connell reaches his destination. He walks into the arena pulling his bag behind him with a white walking cane tapping in front of him.

Oh, did we mention that he does all of that traveling and playing hockey as a blind person?

“I’ve become very good friends with a couple of bus drivers out of Toms River. They think it’s cool. They see the hockey bag,” O’Connell laughed. “You think the world is going to hell or falling apart. I meet all sorts of people. Overwhelmingly, I meet people that want to help me all the time. It gives you a good sense of people.”

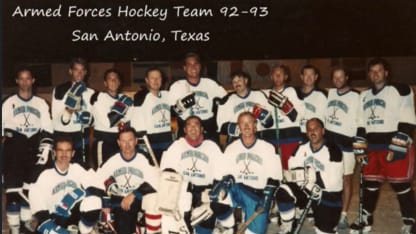

O’Connell, who served over two decades with the U.S. Air Force, plays for the NJ Warriors, a hockey program that gives disabled US military veterans an opportunity to play the sport. The travel isn't easy and sometimes it takes him nearly 12 hours total from the time he leaves his home in the afternoon to when he arrives back at the end of the night. But O'Connell won't let anything stand in the way of his playing the game. Not travel. Not age. Not blindness.

And it is because of his perseverance and dedication to overcome obstacles on and off the ice, O'Connell was named the 2025 USA Hockey Disabled Athlete of the Year.

“It was a real honor,” he said. “You’re invisible to the world as a blind person. It’s just nice that somebody recognizes you. That somebody sees you.”

O’Connell, who will be the Devils’ 'Hero of the Game’ for Monday’s Military Appreciation Night, is legally blind but still has limited eyesight. He can see what’s directly in front of his line of vision, but he can’t see peripherally – so he won’t see people standing right next to him – and has nearly zero vision at night.

Despite those limitations, he didn’t let it interfere with his ability to play hockey. And in many ways, hockey has revitalized his life.

“There are a lot of blind people that become the cat in the window because they have so many close calls (of getting hurt),” he said. “When I first went to (school for the blind), they told me broken bones were going to be part of the deal, just get used to it. So, a lot of people get afraid to go out and have a close call with a car crossing an intersection and say it’s just not worth it.

“Hockey forces me to keep my skills up. It keeps my senses up. It keeps me sharp."

Despite going blind in his 50s, O’Connell never let it be an excuse.

“When you go blind, everyone tells you the things you can’t do,” he said. “You can’t fly an airplane. You can’t drive a car. You can’t work. You can’t do this; you can’t do that. It’s just no, no, no, no.

“But when it came to hockey, no one ever said no to me.”